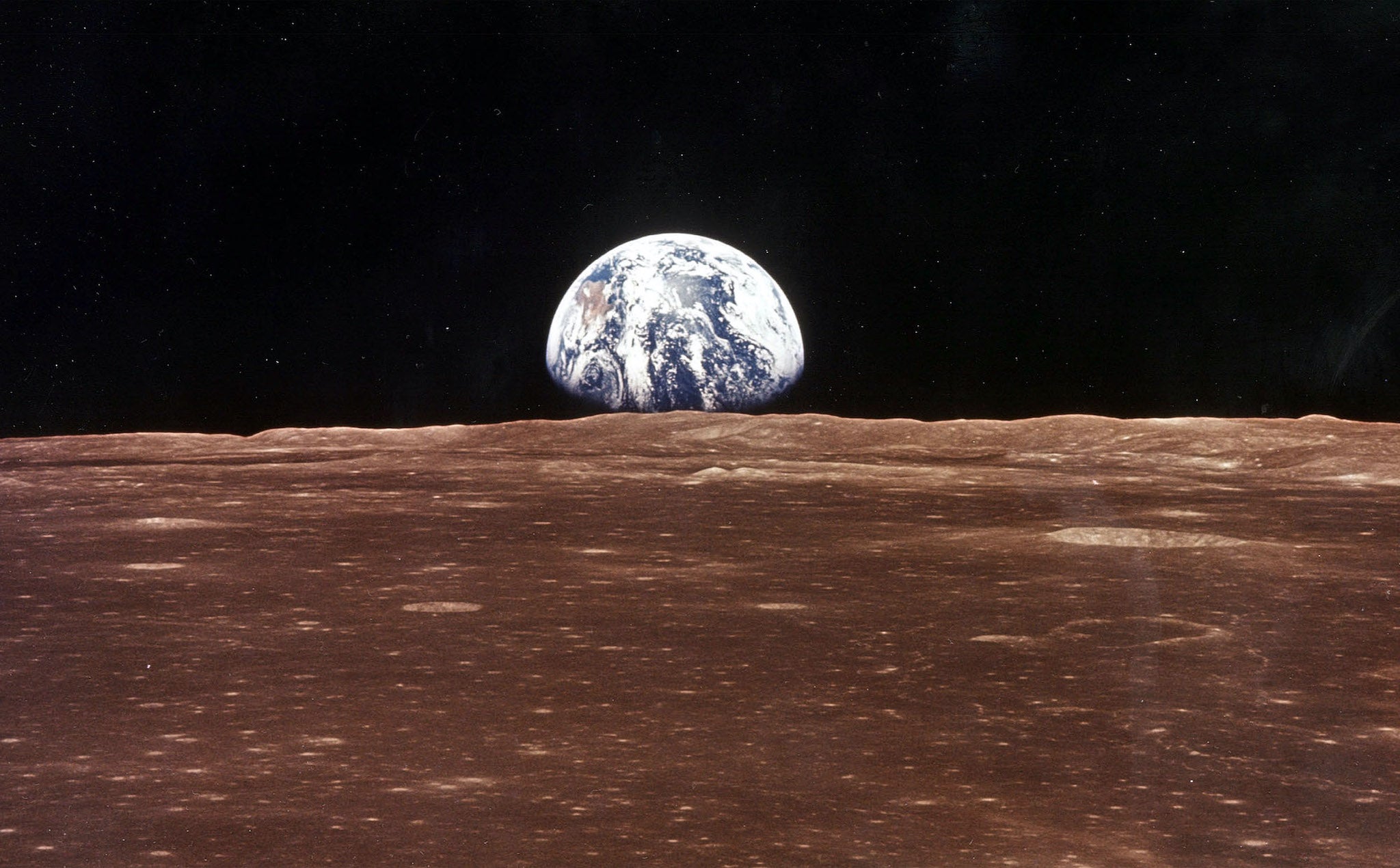

Earth is not necessarily the best planet in the universe for life, a new study has found.

Researchers have found some 24 planets that are “superhabitable”, offering conditions more suitable for life than they are here on Earth.

And some of them even have better stars than our own Sun, the researchers said.

The new study looked for worlds that would be even more likely to foster life than our own – including those that are older, bigger, warmer and wetter than Earth – in the hope of informing future searches for life elsewhere in the universe.

The study identified 24 of the “superhabitable” planets. They are all 100 light years away, making them difficult if not impossible to ever see up close, but research with future telescopes could give us much more information about those worlds.

With technological developments on board upcoming telescopes – such as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, the LUVIOR space observatory and the European Space Agency’s PLATO – researchers hope they may even be able to spot the signatures of life on distance planets.

“With the next space telescopes coming up, we will get more information, so it is important to select some targets,” said Dirk Schulze-Makuch, a professor at Washington State University and the Technical University in Berlin, who led the study.

“We have to focus on certain planets that have the most promising conditions for complex life. However, we have to be careful to not get stuck looking for a second Earth because there could be planets that might be more suitable for life than ours.”

Researchers identified a host of possible criteria for such superhabitable planets. They then looked through the 4,500 known planets outside of our solar system that have been found, in an attempt to identify which could have those important criteria.

That included looking for planets “K dwarf stars”, which are not like out sun. Those similar to our star – known as G stars – only have a relatively short lifespan, and given the Sun was almost half its age before any form of complex life arrived, many other similar planetary systems could die out before they are inhabited.

K dwarf stars, by contrast, are cooler, smaller and brighter than our sun. They also stay around for much longer – up to 70 billion years – meaning that the planets around them would have much more time to develop advanced life, too.

They also looked for planets that are about 10 per cent larger than Earth, with the idea that they are likely to have more habitable land. More mass would also mean that they would keep their interior heating longer, and stronger gravity to keep hold of its atmosphere for more time.

Superhabitable planets would also likely have a little more water than Earth, especially if it was kept as moisture. Being slightly warmer would also make a planet more habitable, with an ideal of about 5 degrees Celsius hotter than Earth thought to be the biggest improvement.

None of the 24 planets described in the study have all of the criteria, despite the vast number to choose from. But one of them has four of those criteria, meaning that it would theoretically be much more accommodating to life and more likely to be inhabited.

“It’s sometimes difficult to convey this principle of superhabitable planets because we think we have the best planet,” said Professor Schulze-Makuch. “We have a great number of complex and diverse lifeforms, and many that can survive in extreme environments. It is good to have adaptable life, but that doesn’t mean that we have the best of everything.”