Professor Emmanuelle Charpentier and Professor Jennifer Doudna have won the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work developing a method for genome editing.

The award takes the number of women who have ever won the Nobel Prize in chemistry from five to seven.

Both scientists will equally share 10 million Swedish kronor (£866,000) for their discovery of “one of gene technology’s sharpest tools” – the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique, or “genetic scissors” as the committee described it.

“Using these [scissors], researchers can change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with extremely high precision,” said the Nobel committee.

“This technology has had a revolutionary impact on the life sciences, is contributing to new cancer therapies and may make the dream of curing inherited diseases come true.”

It is the first time the Nobel Prize for chemistry has been awarded to two women in the same year in its 119-year history.

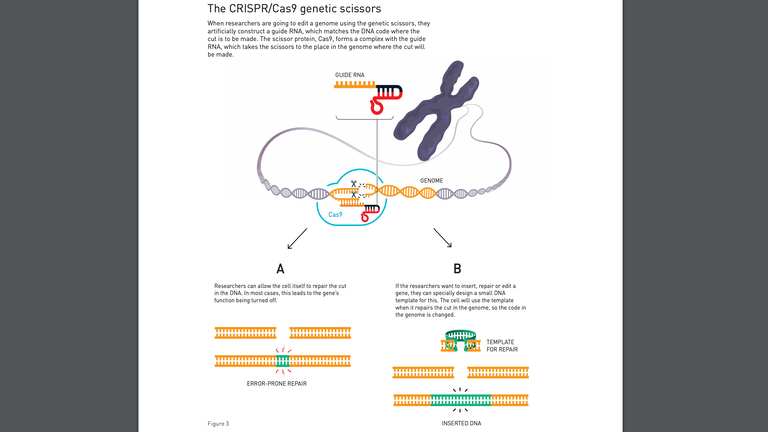

The genome editing technique they developed is based on creating proteins which match the DNA code where a “cut” is going to be made.

This effectively allows researchers to insert, repair or edit a gene in such a way that the DNA doesn’t see the change as damage, but as a legitimate edit to be replicated by the cell.

“There is enormous power in this genetic tool, which affects us all,” said Claes Gustafsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for chemistry.

“It has not only revolutionised basic science, but also resulted in innovative crops and will lead to ground-breaking new medical treatments,”

The discovery was described as an unexpected result of Professor Charpentier studying the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes.

She discovered a previously unknown molecule, tracrRNA, in the bacteria and found that this molecule was part of an ancient immune system, CRISPR/Cas, that disarms viruses by cleaving their DNA.

“Charpentier published her discovery in 2011. The same year, she initiated a collaboration with Jennifer Doudna, an experienced biochemist with vast knowledge of RNA,” the committee reported.

“Together, they succeeded in recreating the bacteria’s genetic scissors in a test tube and simplifying the scissors’ molecular components so they were easier to use,” it added.

“In an epoch-making experiment, they then reprogrammed the genetic scissors.

“In their natural form, the scissors recognise DNA from viruses, but Charpentier and Doudna proved that they could be controlled so that they can cut any DNA molecule at a predetermined site.

“Where the DNA is cut it is then easy to rewrite the code of life,” the Nobel committee added.

Since the scientists discovered these genetic scissors in 2012, the tool has contributed to an enormous range of research, including developing crops that can withstand mould, pests and drought.

In medicine, clinical trials of new cancer therapies are under way, and the dream of being able to “cure inherited diseases is about to come true” the citation concluded.