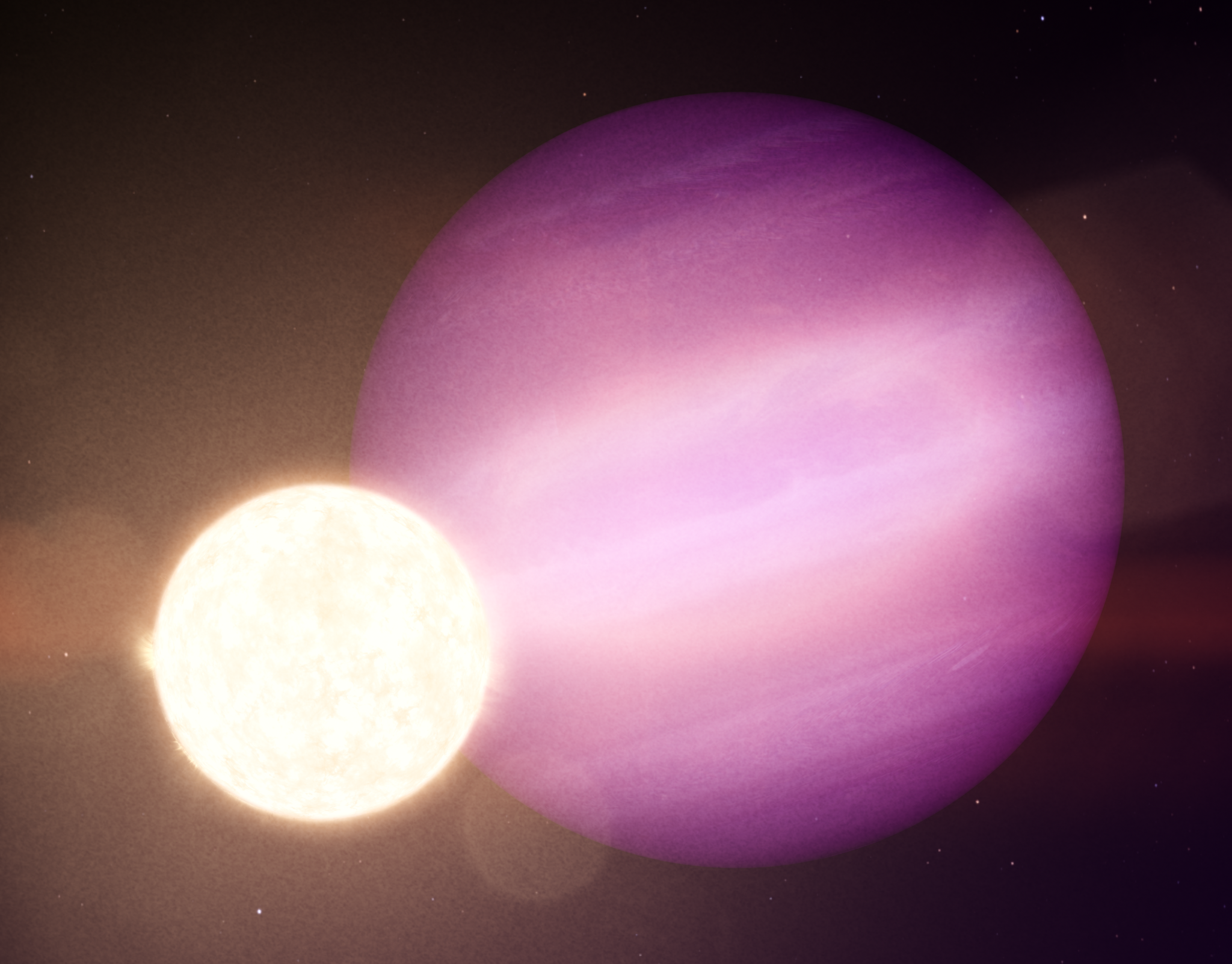

Nasa believes it has found the first ever planet to be closely orbiting around a white dwarf, the leftover of its once Sun-like star.

Some researchers had previously believed that such a search would be fruitless, given that the creation of the white dwarf was expected to destroy any planets that came too close.

But new data from Nasa’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and its retired Spitzer Space Telescope appear to indicate that the planet known as WD 1856 b is intact and in close orbit around its star.

The huge planet – much larger than the star that it orbits around – could offer a hint at what the future of Earth might look like, as well as prompting excitement about the possibility of life on other, similar planets elsewhere in the universe.

“WD 1856 b somehow got very close to its white dwarf and managed to stay in one piece,” said Andrew Vanderburg, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The white dwarf creation process destroys nearby planets, and anything that later gets too close is usually torn apart by the star’s immense gravity.

“We still have many questions about how WD 1856 b arrived at its current location without meeting one of those fates.”

Usually, when a star like our Sun runs out of fuel, it starts to swell up, going to hundreds of thousands of times its previous size, and turns into a cooler red giant. The gas is then thrown out into space, which causes it to shrink down again, casting out 80 per cent of its mass and leaving the remnants behind in the form of a white dwarf.

When that happens, anything that is nearby is usually engulfed and burned away. If WD 1856 b was as close to the star as it is today, it would have suffered the same fate – but researchers speculate that it actually began about 50 times further away, and was pulled in.

“We’ve known for a long time that after white dwarfs are born, distant small objects such as asteroids and comets can scatter inward towards these stars. They’re usually pulled apart by a white dwarf’s strong gravity and turn into a debris disk,” said co-author Siyi Xu, an assistant astronomer at the international Gemini Observatory in Hilo, Hawaii, which is a program of the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab.

“We’ve seen hints that planets could scatter inward, too, but this appears to be the first time we’ve seen a planet that made the whole journey intact.”

WD 1856 b is thought to be no more than 14 times the size of Jupiter, based on the information they were able to gather as it passed in front of the star, as well as the age of the white dwarf itself. Further research is required to confirm that conclusion and allow scientists to decisively know that they have spotted the first such example of a planet in close orbit around a white dwarf.

But it has already led researchers to speculate that if planets are able to survive that dramatic journey, there may be more rocky, Earth-sized planets waiting out there to be found – and that the conditions in orbit around a white dwarf could be favourable to alien life.

“Even more impressively, Webb could detect gas combinations potentially indicating biological activity on such a world in as few as 25 transits,” said Lisa Kaltenegger, the director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute and an author on the paper.

“WD 1856 b suggests planets may survive white dwarfs’ chaotic histories. In the right conditions, those worlds could maintain conditions favorable for life longer than the time scale predicted for Earth. Now we can explore many new intriguing possibilities for worlds orbiting these dead stellar cores.”

An article describing the research, ‘A Giant Planet Candidate Transiting a White Dwarf’, is published in Nature today.