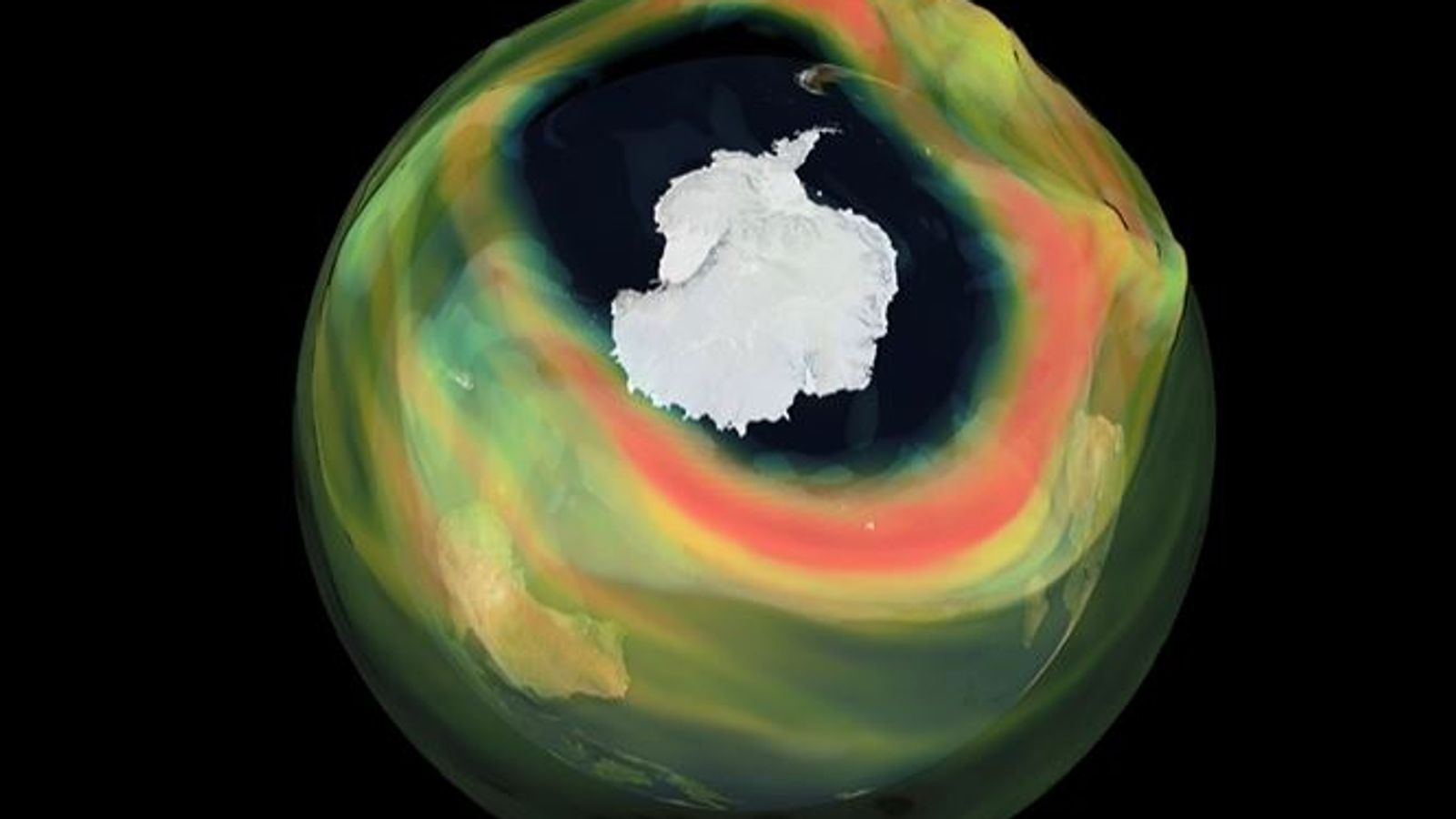

An ozone hole over Antarctica is one of the largest and deepest in recent years, according to scientists.

The ozone layer is a part of the Earth’s atmosphere and acts as a shield, absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

However, chemicals and substances created by humans have led to thinning in the layer, known as ozone holes.

The hole in the ozone layer, which forms annually between September and December over Antarctica, has reached its maximum size for 2020 of around 8.9 million square miles.

Scientists from the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) have said the return of a large hole, following an “unusually small and short-lived” one in 2019, shows the need to enforce the global Montreal Protocol.

This international treaty sets out to protect the ozone layer by banning chemicals, such as CFCs, which cause damage.

These substances, containing chlorine and bromine, accumulate within areas of low pressure, called a polar vortex.

Temperatures in the vortex can fall below -78C (-108.4F), causing the formation of stratospheric clouds which lead to chemical reactions that deplete ozone.

As the sun rises over the South Pole following winter darkness, its energy releases chlorine and bromine atoms in the vortex – these rapidly destroy ozone molecules, leading the hole to form.

Vincent-Henri Peuch, director of CAMS, said: “There is much variability in how far ozone hole events develop each year.

“The 2020 ozone hole resembles the one from 2018, which also was a quite large hole, and is definitely in the upper part of the pack of the last 15 years or so.

“With the sunlight returning to the South Pole in the last weeks, we saw continued ozone depletion over the area.

“After the unusually small and short-lived ozone hole in 2019, which was driven by special meteorological conditions, we are registering a rather large one again this year, which confirms that we need to continue enforcing the Montreal Protocol banning emissions of ozone depleting chemicals.”