Scientists have hailed a new quantum computing breakthrough that could bring the revolutionary technology into the real world.

The discovery could fundamentally change how quantum computers are able to measure energy quanta, which allow the entirely new kind of computers to work.

Quantum computing has long been promised as a way of carrying out computing tasks in vastly quicker ways, potentially changing everything from health research to security.

But they have proven difficult to make practically, not yet fulfilling the promise that their proponents have claimed.

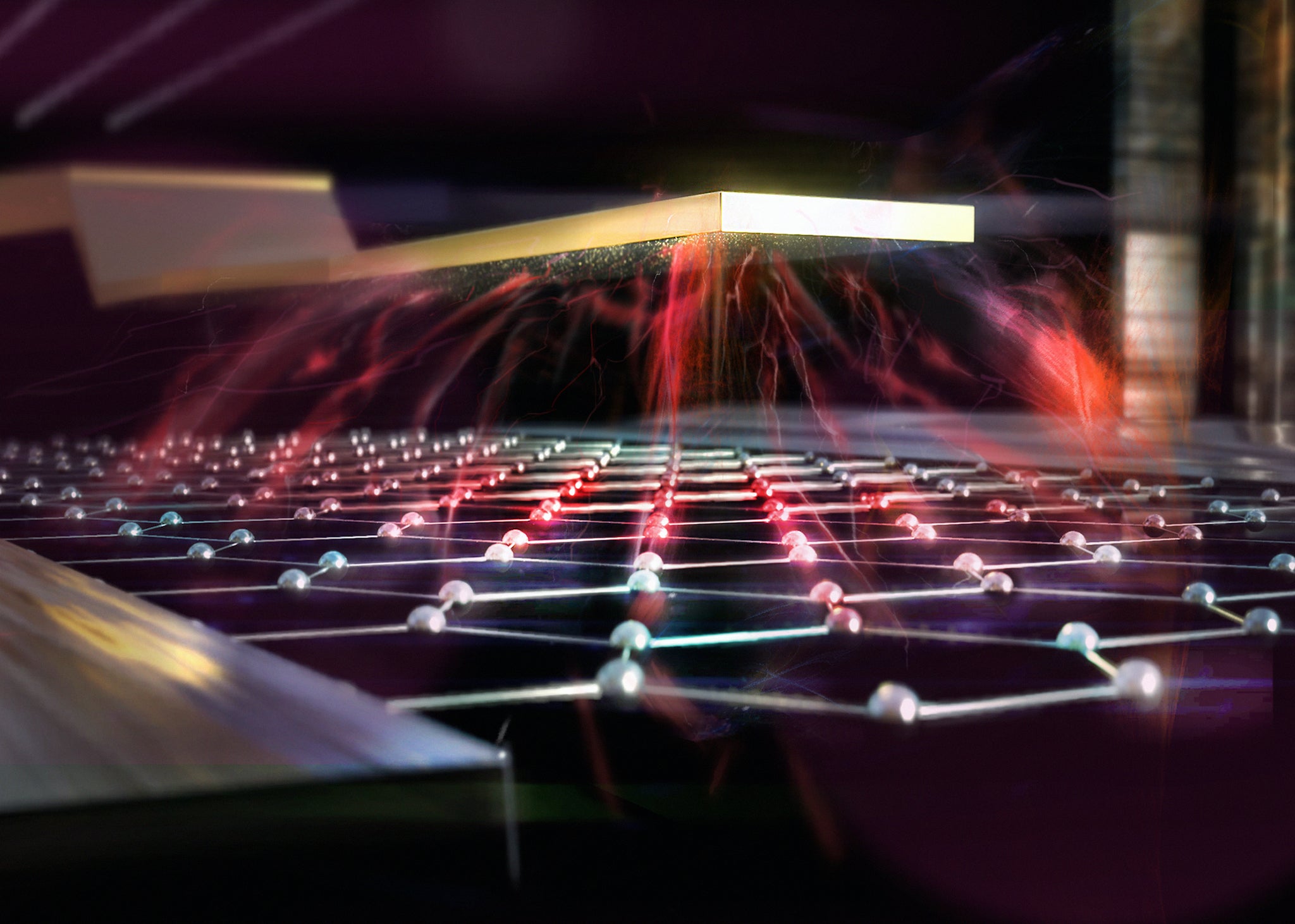

The new breakthrough – described in research newly published in Nature – focuses on a new kind of detector known as a bolometer. That measures the energy of incoming radiation by measuring how much it heats up that detector.

For a quantum computer to work, it must be able to measure the energy state of the qubits that it is made up of.

At the moment, quantum computers generally do so by measuring the voltage induced by the qubit. But that comes with a host of problems, including the need for extensive circuity that could make the computers difficult to scale up and consume power, as well as potentially introducing errors.

By using bolometers, the scientists hope to overcome all of these problems. But until now they have not proven fast or sensitive enough to be actually used practically.

Now the paper describes a new kind of bolometer that could theoretically be included in quantum computers and help bring them into practical use.

‘Bolometers are now entering the field of quantum technology and perhaps their first application could be in reading out the quantum information from qubits. The bolometer speed and accuracy seems now right for it,’ says Mikko Möttönen, the researcher who led the team who made the breakthrough.

Previous bolometers have been made out of a gold-palladium alloy that overcome the noise problems, but was too slow to actually do the work of measuring qubits. Instead, the new research saw engineers create them out of graphene, vastly speeding them up so they are as fast as the current technology.

“Changing to graphene increased the detector speed by 100 times, while the noise level remained the same. After these initial results, there is still a lot of optimisation we can do to make the device even better,” said Pertti Hakonen, who leads a group at Aalto University that has expertise in making graphene-based devices.